Aluminium door and window systems for a golf club extension

From almost the first pencil stroke, KAV’s staff cooperated with Kroki Studio on the extension of the Continental Golf Club. This included a jointly designed support structure, custom latched line-up and skylight connections, amongst other elements of the exclusive building. We spoke to András Göde, one of the founders of Kroki, about the joint work, what it is like to work on the basis of each other’s ideas and the interesting aspects of the project.

What tasks were you invited to carry out in this project?

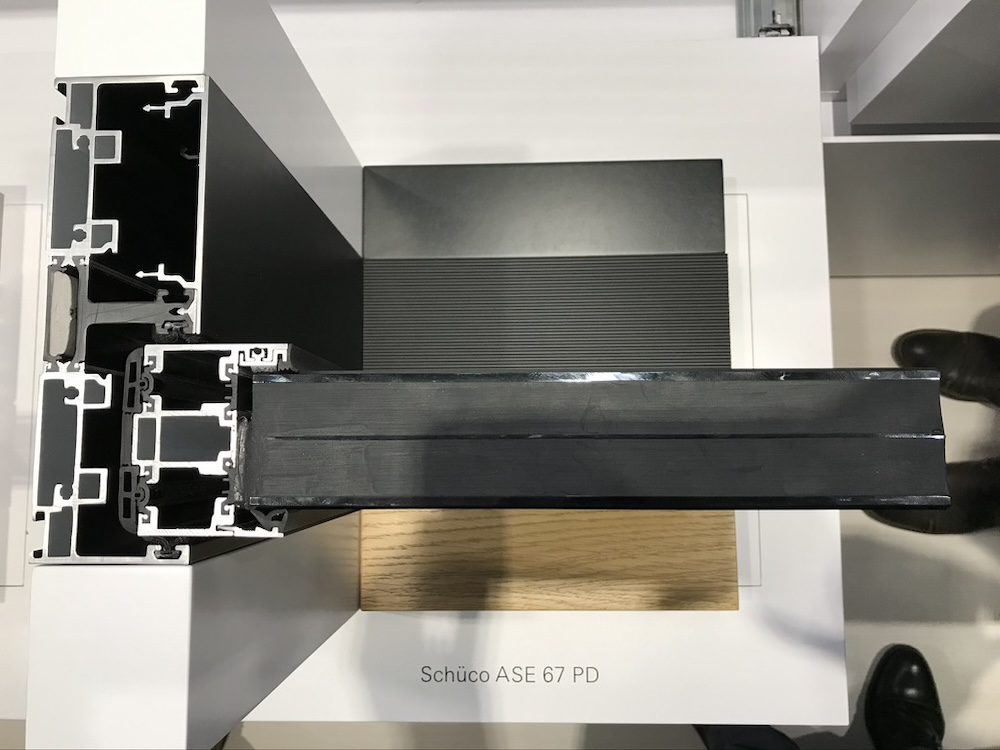

The golf club had an existing building with a restaurant. The new tenant asked us to expand it with an event hall, as there was only a tent there before. The initial idea was to create a simpler, warehouse-style building in terms of appearance, which we would later soup up, both inside and outside. However, we convinced them that it would be a better decision from all points of view to create a building with a beautiful structure, of high quality. So the decision was finally taken to go for a very modern, truly state-of-the-art, timber-panelled system, which requires very precise construction. And, given the structure of the building, we also wanted the glass structure itself to be really high-tech, making the most of the view. We designed large, sliding, elegant glass elements. Because the glass goes from structure to structure, you can’t really hide the junctions, so the installation itself also had to be high-tech. We did the concept design and interior design at Kroki and drew the nodes, while InnoWood, part of Dome Architects, prepared the woodwork construction design. It was here that KAV, who designed the glass structures, joined in. Then these three designer teams and their approaches had to be coordinated, which required quite a lot of consultation, in particular because some of the new structures were placed on the existing building, which required different node solutions. At least 30 nodes were made just to find out how the chosen door and window system could be installed. Thermal, drainage and shading issues were also raised. But it was worth all the consultation, because it’s not only us that’s very satisfied with the final result but also the client. What’s more, the glass walls are indeed visible all the way through, and yet the huge glass panels can be moved, almost by using your little finger.

How did you find KAV, or why exactly did you choose them?

Several companies came up, and we requested bids from three places for the glass structure. The owner was also involved in the decision-making. In the end, references were the deciding factor. All we asked for was to select the supplier in advance so that the technological development could be performed jointly during the design phase. Specialist expertise was necessary in the course of the design. In this way, we could really involve KAV from the outset. Many decisions were made jointly; for example, there was the idea of having a frameless sliding door up to the ceiling, which is obviously a very spectacular thing, but they knew that this would require a completely different type of moving mechanism, which would have been an extra cost that would not have been worth it. Even so, the glass surfaces still move up to a height of 2.40 metres, which is also rather impressive. We were able to go through these decisions by checking what implies what, for which the KAV team and their expertise was absolutely necessary. This is how the decision was made to include a horizontal order of division, which we also had to submit for urban image planning permission, as it is visible on the façade.

It is still rare in Hungary today that the contractor of the windows and doors is involved in the design process, although this would be the ideal process. Why did you think it was important to do so in this case?

It was important, because this is a building constructed by private investors, and in a public procurement it would be impossible to do it in this way. In Hungary, it’s a common construction custom that designs have to be nearly perfect, and then there is a competition to find the manufacturer for it. However, when the manufacturer is found, a lot of corrections are necessary. Somehow everyone has got used to this, which I don’t believe is a good system. If you look at countries where, for example, the process has not been stuck for 40 or 50 years, the system is different. There, the architects more or less know who would be the right contractor for the construction they have come up with. So it’s not the architect who has to know how to fasten the ground sill under the last sliding door, and everything else; it’s the expert who does that. I have an interesting example of this: a Hungarian architect worked in Japan for a very long time, and he said that we Hungarian designers can’t imagine that in Japan it’s the other way round: the contractors don’t try to simplify the plans, but to complicate them. The aim is to make it as challenging as possible, because they can use the building later as a reference. I think that this inverse situation can be achieved if the contractor also approaches the work as a creator. And he wants to show that he’s the best. This is how it happened with this building, and Innowood and KAV joined the work with this attitude. They didn’t want to figure out how to simplify and ‘boil down’ the issue, but the common goal was to make it as good as possible. For this, it was also necessary that the client realised that this is how he would come out of it as a winner. And it’s not good for him to have ready-made designs to put up in a competition to see who the cheapest is.

With KAV joining at the outset, the designs also changed; for example, the first designs included level sliding doors but, due to product changes and the excess weight of the sliding door sashes, skylights were eventually installed. In such a case, how does it affect you when the architectural concept is compromised?

I think a normal architect believes that things need to be proportionate. He doesn’t just think in visual terms. Obviously, a floor to ceiling frameless glass is very elegant. If that’s the core of the architectural idea, he will probably insist on it until his last breath. If it’s not the core of the architectural idea, but something else that contributes to it, then the question arises of how complicated it is to implement and what the costs are. And if it is disproportionate, he changes his mind. In this case, I don’t see it as a compromise because the building has not become a “loser”. It took place proportionately. Moreover, such a building is a business enterprise at the same time. If I design a building for the client that will never show a return afterwards, the design isn’t good because it doesn’t serve the client in functional terms. Here, the investment was obviously higher, but the building can be rented out at a higher price because it’s very high-end one. These have to be joint decisions and, in the ideal case, at the end it will be balanced and neither side will feel put out. Obviously there are compromises that have to be made, but compromises that don’t harm the building.

I understand that finding solutions for the building within the tight deadline also caused a lot of headache …

Yes, for example, it was important when a certain glass surface was to be installed. Because a small robot lifts the glass into its place, but it has to travel through the floor while it may not be sufficiently solid yet. We had to figure out when to pour concrete to make it solid enough for this machine. So the construction process itself was a creative system. Here the architectural concept was very honest; the structures are visible, there are no covers. In such a case, the work has to be completed to a very high standard and with high precision, and this had to be very well thought out in every aspect. The most difficult thing to do is to create an invisible node.

Several unique solutions – latched line up, connection of skylights – have been implemented in this building. What was it like working with a team that could provide realistic and unique answers to these problems?

It was great that KAV and Innowood shared a similar approach. A solution-department rather than a problem-department existed in all of us. When we came up with an idea – say, I wanted to have a connection with a shade slot next to the case – we weren’t told that so and so couldn’t be done, but the things necessary to make it feasible. I felt the same on KAV’s side; if a special solution was needed – for example, a special profile that had not been manufactured before, or the covers on which the shades were to be mounted – they then designed it, manufactured it, and we discussed the implementation and installation steps. We progressed by relying on each other’s ideas in this work.

I wonder, had KAV not drawn up the professional designs, would the work on the windows and doors have been completed to the same quality?

It would have been impossible to do it without these professional designs, because then a lot of problems would have been discovered during installation and the organisation would have failed. Everything had to be thought through in advance. For example, if such designs exist, one can design the connecting elements so that they will be operational. If I want the profile to continue flush with a wall, I need to know everything about the profile, where its edge is, where it can be mounted, in order to know where to put that wall. It’s a game of ping-pong while a process like this goes through, but if it’s not played out, it won’t be flush with the wall.

What are you most proud of about concerning this building?

High-tech solutions have been implemented that are still not intrusive. It was also very important on our part that there was an existing building and a very special location. It’s nearly in the centre of Budapest, yet I can see a huge green park. In a situation like this, we didn’t want the building to intrude too much on nature. When you’re inside you can see the wooden structures, but you can also clearly see what’s around it. The cube stands in the landscape minimally. Standing in the building, I don’t perceive the building, I perceive the landscape, but the building still protects me from the cold and the rain.

In addition, from a sustainability point of view, we wanted a building that was not too expensive to run. To achieve this, we needed three layers of glass in well-insulated aluminium windows. Meanwhile, we were able to incorporate the building already there, which is the past, as an asset. We got to know the architects who designed it and tried to continue with it in a way that can be manufactured on the basis of today’s technology. To fit as much as possible into the contemporary architectural dialogue.

MoreNews